Raúl Alfonsín

Raúl Alfonsín | |

|---|---|

Alfonsín in 1983 | |

| 90th President of Argentina | |

| In office 10 December 1983 – 8 July 1989 | |

| Vice President | Víctor Martínez |

| Preceded by | Reynaldo Bignone |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Menem |

| National Senator | |

| In office 10 December 2001 – 3 July 2002 | |

| Constituency | Buenos Aires |

| Member of the Constitutional Convention | |

| In office 1 May 1994 – 22 August 1994 | |

| Constituency | Buenos Aires |

| National Deputy | |

| In office 25 May 1973 – 24 March 1976 | |

| Constituency | Buenos Aires |

| In office 12 October 1963 – 28 June 1966 | |

| Constituency | Buenos Aires |

| Provincial Deputy of Buenos Aires | |

| In office 1 May 1958 – 29 March 1962 | |

| Constituency | 5th electoral section |

| Councillor of Chascomús | |

| In office 7 May 1954 – 21 September 1955 | |

| Constituency | At-large |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín 12 March 1927 Chascomús, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina |

| Died | 31 March 2009 (aged 82) Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Political party | Radical Civic Union |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 6, including Ricardo Alfonsín |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Awards | |

| Other work(s) | Leader of the Radical Civic Union (1983–1991, 1993–1995, 1999–2001) |

| Signature | |

Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín (Spanish pronunciation: [raˈul alfonˈsin] ⓘ; 12 March 1927 – 31 March 2009) was an Argentine lawyer and statesman who served as President of Argentina from 10 December 1983 to 8 July 1989. He was the first democratically elected president after the 7-years National Reorganization Process. Ideologically, he identified as a radical and a social democrat, serving as the leader of the Radical Civic Union from 1983 to 1991, 1993 to 1995, 1999 to 2001,[not verified in body] with his political approach being known as "Alfonsinism".

Born in Chascomús, Buenos Aires Province, Alfonsín began his studies of law at the National University of La Plata and was a graduate of the University of Buenos Aires. He was affiliated with the Radical Civic Union (UCR), joining the faction of Ricardo Balbín after the party split. He was elected a deputy in the legislature of the Buenos Aires province in 1958, during the presidency of Arturo Frondizi, and a national deputy during the presidency of Arturo Umberto Illia. He opposed both sides of the Dirty War, and several times filed a writ of Habeas corpus, requesting the freedom of victims of forced disappearances, during the National Reorganization Process. He denounced the crimes of the military dictatorships of other countries and opposed the actions of both sides in the Falklands War as well. He became the leader of the UCR after Balbín's death and was the Radical candidate for the presidency in the 1983 elections, which he won.

After becoming president, Alfonsín sent a bill to Congress to revoke the self-amnesty law established by the military. He established the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons to investigate the crimes committed by the military, which led to the Trial of the Juntas and resulted in the sentencing of the heads of the former regime. Discontent within the military led to the mutinies of the Carapintadas, leading him to appease them with the full stop law and the law of Due Obedience. He also had conflicts with the unions, which were controlled by the opposing Justicialist Party. He resolved the Beagle conflict, increased trade with Brazil, and proposed the creation of the Contadora support group to mediate between the United States and Nicaragua. He passed the first divorce law of Argentina. He initiated the Austral plan to improve the national economy, but that plan, as well as the Spring plan, failed. The resulting hyperinflation and riots led to his party's defeat in the 1989 presidential elections, which was won by Peronist Carlos Menem.

Alfonsín continued as the leader of the UCR and opposed the presidency of Carlos Menem. He initiated the Pact of Olivos with Menem to negotiate the terms for the 1994 amendment of the Argentine Constitution. Fernando de la Rúa led a faction of the UCR that opposed the pact, and eventually became president in 1999. Following de la Rúa's resignation during the December 2001 riots, Alfonsín's faction provided the support needed for the Peronist Eduardo Duhalde to be appointed president by the Congress. He died of lung cancer on 31 March 2009, at the age of 82, and was given a large state funeral.

Early life and career

[edit]

Raúl Alfonsín was born on 12 March 1927, in the city of Chascomús, 123 km (76 mi) south of Buenos Aires. His parents, who worked as shopkeepers, were Serafín Raúl Alfonsín Ochoa and Ana María Foulkes. His father was of Galician and German descent,[1] and his mother was the daughter of Welsh immigrant Ricardo Foulkes and Falkland Islander María Elena Ford.[2] Following his elementary schooling, Raúl Alfonsín enrolled at the General San Martín Military Lyceum. Although his father disliked the military, he thought that a military high school would have a similar quality to a private school without being as expensive. Alfonsín disliked the military as well, but this education helped him to understand the military mindset.[3] He graduated after five years as a second lieutenant. He did not pursue a military career and began studying law instead. He began his studies at the National University of La Plata, and completed them at the University of Buenos Aires, graduating at the age of 23. He was not a successful lawyer, he was usually absent from his workplace and frequently in debt.[3] He married María Lorenza Barreneche, whom he met in the 1940s at a masquerade ball, in 1949.[4] They moved to Mendoza, La Plata, and returned to Chascomús. They had six sons, of whom only Ricardo Alfonsín would also follow a political career.[5]

Alfonsín bought a local newspaper (El Imparcial). He joined the Radical Civic Union (UCR) in 1946, as a member of the Intransigent Renewal Movement, a faction of the party that opposed the incorporation of the UCR into the Democratic Union coalition. He was appointed president of the party committee in Chascomús in 1951 and was elected to the city council in 1954. He was detained for a brief time, during the reaction of the government of Juan Perón to the bombing of Plaza de Mayo. The Revolución Libertadora ousted Perón from the national government; Alfonsín was again briefly detained and forced to leave his office in the city council. The UCR broke up into two parties: the Intransigent Radical Civic Union (UCRI), led by Arturo Frondizi, and the People's Radical Civic Union (UCRP), led by Ricardo Balbín and Crisólogo Larralde. Alfonsín did not like the split but opted to follow the UCRP.[6]

Alfonsín was elected deputy for the legislature of the Buenos Aires province in 1958, on the UCRP ticket, and was reelected in 1962. He moved to La Plata, the capital of the province, during his tenure. President Frondizi was ousted by a military coup on 29 March 1962, which also closed the provincial legislature. Alfonsín returned to Chascomús. The UCRP prevailed over the UCRI the following year, leading to the presidency of Arturo Umberto Illia. Alfonsín was elected a national deputy, and then vice president of the UCRP bloc in the congress. In 1963 he was appointed president of the party committee for the province of Buenos Aires.[7] Still in his formative years, Alfonsín was still in low political offices and held no noteworthy role in the administrations of Frondizi and Illia.[8]

Illia was deposed by a new military coup in June 1966, the Argentine Revolution. Alfonsín was detained while trying to hold a political rally in La Plata, and a second time when he tried to re-open the UCRP committee. He was forced to resign as a deputy in November 1966. He was detained a third time in 1968 after a political rally in La Plata. He also wrote opinion articles in newspapers, under the pseudonyms Alfonso Carrido Lura and Serafín Feijó. The Dirty War began during this time, as many guerrilla groups rejected both the right-wing military dictatorship and the civil governments, preferring instead a left-wing dictatorship aligned with the Soviet Union, as in the Cuban Revolution. Alfonsín clarified in his articles that he rejected both the military dictatorship and the guerrillas, asking instead for free elections. The UCRP became the UCR once more, and the UCRI was turned into the Intransigent Party. Alfonsín created the Movement for Renewal and Change within the UCR, to challenge Balbín's leadership of the party. The military dictatorship finally called for free elections, allowing Peronism (which had been banned since 1955) to take part in them. Balbín defeated Alfonsín in the primary elections but lost in the main ones. Alfonsín was elected deputy once more.[9]

Illia was invited in 1975 to a diplomatic mission to the Soviet Union; he declined and proposed Alfonsín instead. Upon his return, Alfonsín became one of the founding members of the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights. He served as the defense lawyer for Mario Roberto Santucho, leader of the ERP guerrillas, but only to carry out due process of law, and not because of a genuine desire to support him.[10] The 1976 Argentine coup d'état against President Isabel Perón started the National Reorganization Process. Alfonsín filed several Habeas corpus motions, requesting the freedom of victims of forced disappearances. The UCR stayed silent over the disappearances, but Alfonsín urged the party to protest the kidnapping of senators Hipólito Yrigoyen (nephew of the former president of the same name) and Mario Anaya.[11] He also visited other countries, denouncing those disappearances and violations of human rights. He established the magazine Propuesta y control in 1976, one of the few magazines that criticized the military dictatorship during its early stages. The magazine was published up to 1978. His editorials were collected in 1980 in the book La cuestión argentina.

Alfonsín expressed opposition to the 1982 Falklands War, criticizing the deployment of troops by both sides during the conflict.[10] He rejected the invasion of the islands, which he considered an inevitable logistic and diplomatic failure, being one of the few politicians who opposed the war from the start.[12] He proposed an emergency government headed by Illia, with ministers from all political parties, who would call for a ceasefire with the British and call for elections.[12] He reasoned that the British would be magnanimous in victory if negotiating the transition with a civilian government, that all Argentine parties would be involved with such negotiations, and provide greater guarantees. The proposal did not get enough support, as Peronist Deolindo Bittel proposed another post-war scenario: electing a prime minister selected by a committee of generals and politicians. In this scenario, the military would keep a veto power and would guide the new government for at least two years. This proposal implicitly intended to remove Bignone and appoint a figure akin to the late Juan Perón, but it did not get support either because the current context did not provide any such figure that would have both support from the military and from the population. Antonio Trocolli, former leader of the Radical Congress, rejected both proposals as impracticable.[13]

The Falklands Wars were lost, and the military lifted the ban on political activities on the promise to hold elections. This was a calculated move to make the politicians focus on internal infighting, instead of blaming the military for the defeat. The plan did not work as intended, as the political parties united in a ad hoc coalition, the "Multipartidaria", that rejected the military attempt to control the new government and asked to speed up the elections, which were called for October 1983.[12] The Movement for Renewal and Change organized the first political event in a stadium in the Buenos Aires suburbs.[14] As Balbín had died in 1981, the UCR had no strong leadership at the time.[15]

Presidential campaign

[edit]

Alfonsín disputed the leadership of the UCR with Carlos Contín, but was unable to pass though the complex internal regulations of the party. He made a new political rally at the Luna Park, with a success comparable to a United States presidential primary. This new rally convinced Contín, who also ambitioned to be president, that he had no chances fighting against Alfonsín in proper primary elections. Fernando de la Rúa, who would have run in the primary elections against him, declined his candidacy because of Alfonsín's huge popularity.[16] Antonio Trocolli, another precandidate, declined to run as well.[14] Alfonsín was then appointed candidate of the UCR for the 1983 general elections, with Víctor Martínez as the candidate for the vice-presidency. The UCR proposed Alfonsín to run with De la Rúa as the candidate for the vice-presidency, to secure the conservative votes, but Alfonsín was confident to win the elections without help.[17]

The publicity was managed by David Ratto, who created the slogan "Ahora Alfonsín" (Spanish: "Now Alfonsín"), and the gesture of shaking hands. His campaign used a non-confrontational approach, in stark contrast with the Peronist candidate for the governorship of the Buenos Aires province, Herminio Iglesias. Iglesias burned a coffin with the seals of the UCR on live television, which generated a political scandal. Both Iglesias and Ítalo Luder, the Peronist candidate for the presidency, saw a decrease in their public image as a result.[16] A group of UCR supporters drew graffiti that praised Alfonsín manliness and mocked Luder as effeminate; Alfonsín ordered to remove the graffitis as soon as he knew about them.[17]

During the campaign, both parties made similar proposals to reduce authoritarianism and the political influence of the military, and to maintain the Argentine claim in the Falkland Islands sovereignty dispute.[18] Alfonsín denounced a pact between the military and the Peronist unions that sought an amnesty for the military. He maintained that the armed forces should be subject to the civilian government and that unions should be regulated. He also proposed an investigation into the actions of the military during the Dirty War. He closed his campaign by reading the preamble of the constitution of Argentina.[19] The last rally was at the Plaza de la República, and was attended by 400,000 people.[20] Opinion polls placed the UCR behind the PJ, but also placed Alfonsín as the most popular politician at the time.[14]

The elections were held on 30 October. The Alfonsín–Martínez ticket won with 51.7% of the vote, followed by Luder–Bittel with 40.1%. It was the first time since the rise of Juan Domingo Perón that the Peronist party was defeated in elections without electoral fraud or proscription. The UCR won 128 seats in the Assembly, forming a majority; and 18 seats in the Senate, constituting a minority. 18 provinces elected radical governors and 17 elected governors from either the Justicialist or local parties. Alfonsín took office on 10 December and gave a speech from the Buenos Aires Cabildo.[21]

Presidency

[edit]First days

[edit]

The presidential inauguration of Alfonsín was attended by Isabel Perón. Despite internal recriminations for the defeat, the Peronist party agreed to support Alfonsín as president, to prevent a return of the military. There were still factions in the military ambitious to keep an authoritarian government, and groups such as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo seeking reparations for the actions of the military during the Dirty War.[22]

Three days after taking office, Alfonsín sent a bill to Congress to revoke the self-amnesty law established by the military. This made it possible for the judiciary to investigate the crimes committed during the Dirty War.[23] During the campaign, Alfonsín had promised that he would do this while Luder had been non-committal.[24] Alfonsín also ordered the initiation of judicial cases against guerrilla leaders Mario Firmenich, Fernando Vaca Narvaja, Ricardo Obregón Cano, Rodolfo Galimberti, Roberto Perdía, Héctor Pardo and Enrique Gorriarán Merlo; and military leaders Jorge Videla, Emilio Massera, Orlando Agosti, Roberto Viola, Armando Lambruschini, Omar Graffigna, Leopoldo Galtieri, Jorge Anaya and Basilio Lami Dozo.[23] He also requested the extradition of guerrilla leaders who were living abroad.[25]

Most of the first cabinet, organized in Chascomús, was composed of trusted colleagues of Alfonsín. Alfonsín appointed as minister of labor Antonio Mucci, who belonged to a faction of the UCR that sought to reduce the influence of Peronism among labor unions, and promptly sent a bill to Congress designed to promote independent unions.[26] Facing an economic crisis, he appointed Bernardo Grinspun as minister of the economy.[27] He appointed Aldo Neri minister of health, Dante Caputo minister of foreign relations, Antonio Tróccoli minister of interior affairs, Roque Carranza minister of public works, Carlos Alconada Aramburu minister of education, and Raúl Borrás minister of defense. Juan Carlos Pugliese led the chamber of deputies, and Edison Otero was the provisional president of the senate. Many presidential negotiations took place at the Quinta de Olivos, the official residence of the president, rather than at the Casa Rosada.[28]

Aftermath of the Dirty War

[edit]

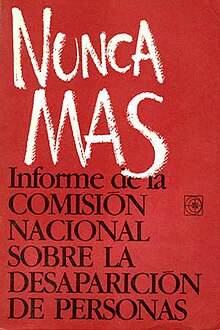

The priority of Raúl Alfonsín was to consolidate democracy, incorporate the armed forces into their standard role in a civilian government, and prevent further military coups.[29] Alfonsín first tried to reduce the political power of the military with budget cuts, reductions of military personnel and changing their political tasks.[30] As for the crimes committed during the Dirty War, Alfonsín was willing to respect the command responsibility and accept the "superior orders" defense for the military of lower ranks, as long as the Junta leaders were sentenced under military justice. This project was resisted by human rights organizations such as Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and public opinion,[31] as it was expected that the defendants would be acquitted or receive low sentences.[25] The military considered that the Dirty War was legally sanctioned, and considered the prosecutions to be unjustified.[25] Alfonsín also established the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), composed of several well-known personalities, to document cases of forced disappearances, human rights violations and abduction of children.[23] Alfonsín sent a military code bill to Congress so that the military would use it. In its "Nunca más" report (Spanish: Never again), the CONADEP revealed the wide scope of the crimes committed during the Dirty War, and how the Supreme Council of the military had supported the military's actions against the guerrillas.[32]

As a result, Alfonsín sponsored the Trial of the Juntas, in which, for the first time, the leaders of a military coup in Argentina were on trial.[33] The first hearings began at the Supreme Court in April 1985 and lasted for the remainder of the year. In December, the tribunal handed down life sentences for Jorge Videla and former Navy Chief Emilio Massera, as well as 17-year sentences for Roberto Eduardo Viola. President Leopoldo Galtieri was acquitted of charges related to the repression, but he was court-martialed in May 1986 for malfeasance during the Falklands War.[34] Ramón Camps received a 25-year sentence. The trials did not focus only on the military: Mario Firmenich was captured in Brazil in 1984 and extradited to Argentina. José López Rega was extradited from Miami in 1986, because of his links with the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance.[35]

The military was supported by the families of the victims of subversion, a group created to counter the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. This group placed the blame for the Dirty War on the guerrillas but had few followers.[36] The trials were followed by bomb attacks and rumors of military protests and even a possible coup. Alfonsín sought to appease the military by raising their budget. As that was not enough, he proposed the full stop law, to set a deadline for Dirty War-related prosecutions. The Congress approved the law, despite strong opposition from the public. Prosecutors rushed to start cases before the deadline, filing 487 charges against 300 officers, with 100 of them still in active service. Major Ernesto Barreiro refused to appear in court and started a mutiny in Córdoba. Lieutenant Colonel Aldo Rico started another mutiny at Campo de Mayo, supporting Barreiro. The rebels were called "Carapintadas" (Spanish: "Painted faces") because of their use of military camouflage. The CGT called a general strike in support of Alfonsín, and large masses rallied in the Plaza de Mayo to support the government. Alfonsín negotiated directly with the rebels and secured their surrender. He announced the end of the crisis from the balcony of the Casa Rosada.[37] The mutineers eventually surrendered, but the government proceeded with the Law of Due Obedience to regulate the trials. However, the timing of both events was exploited by the military, and the opposition parties described the outcome as a surrender by Alfonsín.[38]

Aldo Rico escaped from prison in January 1988 and started a new mutiny in a distant regiment in the northeast. This time, both the military support for the mutiny and the public outcry against it were minimal. The army attacked him, and Rico surrendered after a brief combat. Colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín launched a new mutiny in late 1988. As in 1987, the mutineers were defeated and jailed, but the military was reluctant to open fire against them. Alfonsín's goal of reconciling the military with the civil population failed, as the latter rejected the military's complaints, and the military was focused on internal issues. The Movimiento Todos por la Patria, a small guerrilla army led by Enrique Gorriarán Merlo, staged the attack on the Regiment of La Tablada in 1989. The army killed many of its members and quickly defeated the uprising.[39]

Relation with trade unions

[edit]

During his tenure, Alfonsin clashed with labor unions in Argentina over economic reforms and trade liberalization policies.[40] Peronism still controlled the labor unions, the most powerful ones in all of Latin America.[18] The biggest one was the General Confederation of Labour (CGT). Alfonsín sought to reduce the Peronist influence over the unions, fearing that they may become a destabilizing force for the fledgling democracy.[41] He rejected their custom of holding single-candidate internal elections, and deemed them totalitarian and not genuine representatives of the workforce. He proposed to change the laws for those internal elections, remove the union leaders appointed during the dictatorship, and elect new ones under the new laws.[42] The CGT rejected the proposal as interventionist, and prompted Peronist politicians to vote against it.[43] The law was approved by the Chamber of Deputies but failed to pass in the Senate by one vote.[44] A second bill proposed simply a call to elections, without supervision from the government, which was approved. As a result, the unions remained Peronist.[45]

The CGT was splintered into internal factions at the time. Lorenzo Miguel had close ties to the Justicialist party, and led "the 62 organizations" faction. Saúl Ubaldini was more confrontational, distrusted the politicians of the PJ, and was eventually appointed secretary general of the CGT.[44] His lack of political ties allowed him to work as a mediator between the union factions. Carlos Alderete led a faction closer to Alfonsín, named "the 15" unions. The government sought to deepen the internal divisions between the unions by appointing Alderete as minister of labor and promoting legislation to benefit his faction. He was removed after the defeat in the 1987 midterm elections, but the government stayed on good terms with his faction.[46]

Alfonsín kept a regulation from the dictatorship that allowed him to regulate the level of wages. He authorized wage increases every three months, to keep them up to the inflation rate. The CGT rejected this, and proposed instead that wages be determined by free negotiations.[47] Alfonsín allowed strike actions, which were forbidden during the dictatorship, which gave the unions another way to expand their influence.[48] There were thirteen general strikes and thousands of minor labor conflicts. However, unlike similar situations in the past, the CGT sided with Alfonsín during the military rebellions, and did not support the removal of a non-Peronist president.[43][49] The conflicts were caused by high inflation, and the unions requested higher wages in response to it. The unions got the support of the non-unionized retirees, the church and left-wing factions. Popular support for the government allowed it to endure despite opposition from the unions.[50]

Social policies

[edit]With the end of the military dictatorship, Alfonsín pursued cultural and educational policies aimed at reducing the authoritarian customs of several institutions and groups. He also promoted freedom of the press. Several intellectuals and scientists who had left the country in the previous decade returned, which benefited the universities. The University of Buenos Aires returned to the quality levels that it had in the 1960s. Many intellectuals became involved in politics as well, providing a cultural perspective to the political discourse. Both Alfonsín and the Peronist Antonio Cafiero benefited.[51]

Divorce was legalized by a law passed in 1987. The church opposed it, but it had huge popular support that included even Catholic factions, who reasoned that marital separation already existed, and divorce simply made it explicit. The church opposed Alfonsín after that point. The church successfully exerted pressure to prevent the abolition of religious education. In line with the teachings of Pope John Paul II, the Church criticized what it perceived as an increase in drugs, terrorism, abortion, and pornography.[52] Alfonsín also intended to decriminalize abortion but dropped the idea to prevent further clashes with the Church.[17]

Foreign policy

[edit]

Argentina had a tense relationship with the United Kingdom due to the recently concluded Falklands War. The British government had temporarily prohibited all foreign ships from entering the exclusion zone of the islands in 1986. Argentina organized air and marine patrols, as well as military maneuvers in Patagonia. However, this was not enough to placate the military hard-liners in Argentina.[35] Alfonsín proposed the postponement of the sovereignty discussions, instead negotiating for a de jure cease of hostilities, with a reduction in the number of military forces and normalization of Argentina–United Kingdom relations. The United Kingdom did not trust the proposal, suspecting that it was a cover-up for sovereignty discussions.[53]

The Beagle conflict was still an unresolved problem with Chile, despite the 1978 Papal mediation. The military, troubled by the trial of the juntas, called for rejection of the proposed agreement and a continuation of the country's claim over the islands. Alfonsín called for a referendum to settle the dispute. Despite opposition from the military and the Justicialist party, who called for abstention, support for the resolution referendum reached 82%.[54] The bill passed in the Senate by a single vote majority, as the PJ maintained its resistance. The Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina was signed the following year, ending the conflict. The human rights violations committed by the Chilean president Augusto Pinochet remained a contentious issue, as well as the revelation of Chilean assistance to British forces during the Falklands War.[55] The Argentine church invited Pope John Paul II for a second visit to Argentina in 1987, to celebrate his successful mediation. He celebrated World Youth Day next to the Obelisk of Buenos Aires, and gave a mass at the Basilica of Our Lady of Luján.[56]

Argentina allied with Brazil, Uruguay and Peru, three countries that had also recently ended their local military dictatorships, to mediate in the conflict between the United States and Nicaragua.[57] They created the Contadora support group, to support the Contadora group from South America. Both groups negotiated together but ultimately failed because of the reluctance of both Nicaragua and the United States to change their positions. The group changed its scope later to discuss foreign debt and diplomacy with the United Kingdom concerning the Falklands conflict.[58]

Initially, Alfonsín refused to foster diplomatic relations with the Brazilian military government, and only did so when the dictatorship ended and José Sarney became president. One of their initial concerns was to increase Argentine–Brazilian trade. Both presidents met in Foz do Iguaçu and issued a joint declaration about the peaceful use of nuclear power. A second meeting in Buenos Aires strengthened the trade agreements. Argentina and Brazil signed the Program of Integration and Economic Cooperation (PICE),[59] and in 1988 both countries and Uruguay agreed to create a common market. This led to the 1991 Treaty of Asunción, that created the Mercosur.[60]

Alfonsín was the first Argentine head of state to give an official visit to the USSR.

Economic policy

[edit]

Alfonsín began his term with many economic problems. In the previous decade, the national economy had contracted by 15%.[61] The foreign debt was nearly 43 billion dollars by the end of the year, and the country had narrowly prevented a sovereign default in 1982. During that year, the gross domestic product fell by 5.6%, and the manufacturing profits by 55%. Unemployment was at nearly 10%, and inflation was nearly 209%. It also appeared unlikely that the country would receive the needed foreign investment.[62] The country had a deficit of $6.7 billion. Possible solutions such as a devaluation of the currency, privatization of industry, or restrictions on imports, would probably have proven to be unpopular.[27]

Initially, the government did not take any strong action to tackle the economic problems.[61] Bernardo Grinspun, the first minister of the economy, arranged an increase in wages, reaching the levels of 1975. This caused inflation to reach 32%. He also tried to negotiate more favorable terms on the country's foreign debt, but the negotiations failed. Risking a default, he negotiated with the IMF, which requested spending cuts. International credits prevented default at the end of 1984, but he resigned in March 1985 when the debt reached $1 billion and the IMF denied further credits. Grinspun was succeeded by Juan Vital Sourrouille, who designed the Austral plan in 1985. This plan froze prices and wages, stopped the printing of money, arranged spending cuts, and established a new currency, the Austral, worth 1 United States dollar. The plan was a success in the short term and choked inflation.[63] However, most of the initial popularity of Alfonsín had declined by this point, and could not persuade many of the benefits of austerity for the long-term improvement of the economy.[61] Inflation rose again by the end of the year, the CGT opposed the wage freeze, and the business community opposed the price freeze. Alfonsín thought that the privatization of some state assets and deregulation of the economy might work, but those proposals were opposed by both the PJ and his own party.[64] The Austral plan was also undermined by populist economic policies held by the government.[61]

With the support of the World Bank, the government tried new measures in 1987, including an increase in taxes, privatizations, and a decrease in government spending. Those measures could not be enforced; the government had lost the 1987 midterm elections, "the 15" unions that had earlier supported the government distanced themselves from it, and the business community was unable to suggest a clear course of action. The PJ, aiming for a victory in the 1989 presidential elections, opposed the measures that it believed would have a negative social impact.[65] The "Spring plan" sought to keep the economy stable until the elections by freezing prices and wages and reducing the federal deficit. This plan had an even worse reception than the Austral plan, and none of the parties supported it. The World Bank and the IMF refused to extend credits to Argentina. Big exporters refused to sell dollars to the Central Bank, which depleted its reserves.[66] The austral was devaluated in February 1989, and the high inflation turned into hyperinflation. The US Dollar was worth 14 Australes by the beginning of 1989, and 17000 by May.[61] The 1989 presidential elections took place during this crisis, and the Justicialist Carlos Menem became the new president.[67]

Midterm elections

[edit]The actions taken against the military contributed to a strong showing by the UCR in the November 1985 legislative elections. They gained one seat in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Congress, which meant control of 130 of the 254 seats. The Justicialists lost eight seats (leaving 103) and smaller, provincial parties made up the difference. Alfonsín surprised observers in April 1986 by announcing the creation of a panel entrusted to plan a transfer of the nation's capital to Viedma, a small coastal city 800 km (500 mi) south of Buenos Aires. This proposal was never implemented, as it was too expensive because Viedma lacked the required urban infrastructure.[68] His proposals boldly called for constitutional amendments creating a Parliamentary system, including a prime minister, and were well received by the Chamber of Deputies, though they encountered strong opposition in the Senate.[69]

The government suffered a big setback in the 1987 legislative election. The UCR lost the majority in the chamber of deputies. All provinces elected Peronist governors, except for Córdoba and Río Negro. Along with the city of Buenos Aires (a federal district at the time), they were the only districts where the UCR prevailed. As a result, the government could not move forward with its legislative agenda, and the PJ only supported minor projects. The PJ was strengthened for the 1989 presidential elections, and the UCR sought to propose governor Eduardo Angeloz as a candidate. Angeloz was a rival of Alfonsín within the party.[70]

Later years

[edit]

Amid rampant inflation, Angeloz was heavily defeated by PJ candidate Carlos Menem in the 1989 election. By the winter of 1989, the inflation had grown so severe that Alfonsín transferred power to Menem on 8 July, five months earlier than scheduled.

Alfonsín stayed on as president of the UCR, leaving after the party's defeat in the 1991 legislative elections. Suffering damage to its image because of the hyperinflation of 1989, the UCR lost in several districts. Alfonsín became president of the party again in 1993. He supported the creation of a special budget for the province of Buenos Aires, led by governor Eduardo Duhalde. The radical legislator Leopoldo Moreau supported the new budget even more vehemently than the Peronists. Both parties had an informal alliance in the province. Alfonsín also supported the amendment to the constitution of Buenos Aires that allowed Duhalde to run for re-election.[71]

President Carlos Menem sought a constitutional amendment to allow his re-election, and Alfonsín opposed it. The victory in the 1993 midterm elections strengthened the PJ, which approved the bill in the Senate. Menem proposed a referendum on the amendment, to force the radical deputies to support it. He also proposed a bill for a law that would allow a constitutional amendment with a simple majority of the Congress.[72] As a result, Alfonsín made the Pact of Olivos with him. With this agreement, the UCR would support Menem's proposal, but with further amendments that would reduce presidential power. The Council of Magistracy of the Nation reduced the influence of the executive power over the judiciary, the city of Buenos Aires would become an autonomous territory allowed to elect its mayor, and the presidential term of office would be reduced to four years. The presidential elections would include the two-round system, and the electoral college would be abolished. Alfonsín was elected to the constituent assembly that worked for the 1994 amendment of the Argentine Constitution. A faction of the UCR, led by Fernando de la Rúa, opposed the pact, but the party as a whole supported Alfonsín.[73] The UCR got only 19% of the vote in the elections, attaining a third position in the 1995 presidential elections behind the Frepaso when Menem was re-elected. Alfonsín resigned the presidency of the party in that year.[74]

The UCR and the Frepaso united as a political coalition, the Alliance for Work, Justice, and Education, led by Alfonsín, Fernando de la Rúa, and Rodolfo Terragno from the UCR, and Carlos Álvarez and Graciela Fernández Meijide from the Frepaso. The coalition won the 1997 legislative elections.[75] Alfonsín did not agree with de la Rúa about the fixed exchange rate used by then. He thought that it had been a good measure in the past but had become detrimental to the Argentine economy, while de la Rúa supported it.[76]

Alfonsín suffered a car crash in the Río Negro province in 1999, during the campaign for governor Pablo Verani. They were on Route 6, and he was ejected from the car because he was not wearing a seat belt. He was hospitalized for 39 days. De la Rúa became president in the 1999 elections, defeating the governor of Buenos Aires, Eduardo Duhalde. Alfonsín was elected Senator for Buenos Aires Province in October 2001. De la Rúa resigned during the December 2001 riots, and the Congress appointed Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, who resigned as well. Alfonsín instructed the Radical legislators to support Duhalde as the new president. He also gave him two ministers, Horacio Jaunarena for Defense and Jorge Vanossi for Justice. The radical support helped Duhalde overcome the ambitions of Carlos Ruckauf and José Manuel de la Sota, who also had ambitions to be appointed president.[77] Alfonsín's health problems later in the year led him to step down, to be replaced by Diana Conti.[78]

In 2006, Alfonsín supported a faction of the UCR that favored the idea of carrying an independent candidate for the 2007 presidential elections. The UCR, instead of fielding its own candidate, endorsed Roberto Lavagna, a center-left economist who presided over the recovery in the Argentine economy from 2002 until he parted ways with President Néstor Kirchner in December 2005. Unable to sway enough disaffected Kirchner supporters, Lavagna garnered third place.[79] Alfonsín was honored by President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner with a bust of his likeness at the Casa Rosada on 1 October 2008. This was his last public appearance.[80]

Death

[edit]

Alfonsín died at home on 31 March 2009, at the age of 82, after being diagnosed a year before with lung cancer. The streets around his house at the Santa Fe avenue were filled with hundreds of people, who started a candlelight vigil. The radical Julio Cobos, Fernández de Kirchner's vice president, was the acting president at the moment and ordered three days of national mourning. There was a ceremony in the Congress, where his body was displayed in the Blue Hall, that was attended by almost a thousand people.[81] His widow María Lorenza Barreneche could not attend the funeral, because of her own poor health.[82] It was attended by former presidents Carlos Menem, Fernando de la Rúa, Eduardo Duhalde and Néstor Kirchner, all the members of the Supreme Court of Argentina, mayor Mauricio Macri, governor Daniel Scioli, the president of Uruguay Tabaré Vázquez and several other politicians. The coffin was moved to La Recoleta Cemetery. He was placed next to the graves of other important historical figures of the UCR, such as Leandro N. Alem, Hipólito Yrigoyen and Arturo Illia.[83]

At the international level, Perú set a day of national mourning, and Paraguay set three days. The governments of Brazil, Chile, Colombia, France, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Spain, Uruguay, and the United States sent messages of condolence.[84] In addition to Tabaré Vázquez, Julio María Sanguinetti of Uruguay, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil attended the ceremony.[83]

Legacy

[edit]

Historians Félix Luna, Miguel Angel de Marco, and Fernando Rocchi all praise the role of Raúl Alfonsín in the aftermath of the Dirty War and the restoration of democracy. Luna also considers that Alfonsín was an effective president and that he set an example of not using the state for personal profit. De Marco points out that it was a delicate time, and any mistake could have endangered the newly founded democracy and led to another coup.[85] The aforementioned historians do not agree, though, on their view of the Pact of Olivos. Luna considers that it was a necessary evil to prevent the chaos that would have been generated if Menem managed to proceed with the constitutional amendment without negotiating with the UCR. De Marco and Rocchi instead believe that it was the biggest mistake of Alfonsín's political career.[85]

Alfonsín received the 1985 Princess of Asturias Award for international cooperation because of both his role in ending the Beagle dispute and his work to reestablish democracy in Argentina. He was named "Illustrious Citizen of Buenos Aires Province" in 2008, and "Illustrious Citizen of Buenos Aires" in 2009. The latter award was granted posthumously and received by his son Ricardo Alfonsín, ambassador to Spain.[86]

Publications

[edit]- La cuestión argentina. Propuesta Argentina. 1981. ISBN 9505490488.[87]

- Qué es el radicalismo. Círculo de lectores. 1983. ISBN 9500701812.[87]

- Ahora: mi propuesta política. Sudamericana. 1983. ISBN 9503700086.[87]

- Inédito: una batalla contra la dictadura. Legasa. 1986. ISBN 9506000883.[87]

- El poder de la democracia. Fundación Plural. 1987. ISBN 9509910902.[87]

- Política social y democracia: la experiencia del cono sur. Intercontinental. 1993. ISBN 987917318X.[87]

- Democracia y consenso. Consejo Económico y Social. 1996. ISBN 9500509148.[87]

- Memoria política: transición a la democracia y derechos humanos. Fondo de Cultura Económica. 2004. ISBN 950557617X.[87]

- Fundamentos de la república democrática: curso de teoría del estado. Eudeba. 2006. ISBN 9502315626.[87]

References

[edit]- ^ Lagleyze, p. 8

- ^ Quirós, Carlos Alberto (1986). Guía Radical. Galerna. p. 13. ISBN 9789505561858.

- ^ a b Burns, p. 116

- ^ "Murió María Lorenza Barrenechea, la esposa de Raúl Alfonsín". Clarín (Argentine newspaper). 6 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 9–10

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 10–13

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 13–14

- ^ Burns, p. 119

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 14–19

- ^ a b Rock, p. 387

- ^ Burns, p. 120

- ^ a b c Burns, p. 124

- ^ Burns, p. 125

- ^ a b c Burns, p. 126

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 20–23

- ^ a b Lagleyze, p. 23

- ^ a b c Rodrigo Duarte (12 October 2017). "Diez anécdotas de Alfonsín, el padre de la democracia moderna en Argentina" [Ten anecdotes of Alfonsín, the father of modern democracy in Argentina] (in Spanish). Infobae. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ a b Rock, p. 388

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 23–26

- ^ Rock, 389

- ^ Lagleyze, p. 26

- ^ Rock, p. 390

- ^ a b c Tedesco, p. 66

- ^ Méndez, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c Lewis, p. 152

- ^ Tedesco, pp. 73–74

- ^ a b Lewis, p. 148

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 32–33

- ^ Tedesco, p. 62

- ^ Tedesco, p. 64

- ^ Tedesco, p. 65

- ^ Tedesco, pp. 67–68

- ^ Tedesco, p. 68

- ^ Rock, p. 395

- ^ a b Rock, p. 401

- ^ Lewis, p. 154

- ^ Lewis, pp. 154–155

- ^ Romero, p. 251

- ^ Romero, pp. 264–265

- ^ Dean, Adam (2022), "Opening Argentina: Menem's Repression of the CGT", Opening Up by Cracking Down: Labor Repression and Trade Liberalization in Democratic Developing Countries, Cambridge University Press, pp. 113–147, doi:10.1017/9781108777964.007, ISBN 978-1-108-47851-9

- ^ Tedesco, pp. 62–63

- ^ Tedesco, pp. 71–72

- ^ a b Tedesco, p. 73

- ^ a b Lewis, p. 156

- ^ Rock, p. 397

- ^ Romero, p. 253

- ^ Tedesco, p. 72

- ^ Rock, 391

- ^ Lewis, p. 155

- ^ Romero, pp. 252–253

- ^ Romero, pp. 245–246

- ^ Romero, pp. 246–247

- ^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros (2000). "Enero de 1984-julio de 1989" [January 1984 – July 1989] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Lewis, pp. 153–154

- ^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros (2000). "Las relaciones con los países latinoamericanos" [Relation with Latin American countries] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ "Las visitas de Juan Pablo II a la Argentina" [The visits of John Paul II to Argentina] (in Spanish). La Nación. 1 April 2005. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Romero, p. 247

- ^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros (2000). "El Grupo de Contadora y el Grupo de Apoyo a Contadora: el Grupo de los Ocho" [The Contadora group and the Contadora support group: the group of the eight] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros (2000). "Las relaciones con Brasil" [The relations with Brazil] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros (2000). "Las relaciones con Uruguay" [The relations with Uruguay] (in Spanish). CARI. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Hedges, p. 245

- ^ Rock, p. 391

- ^ Rock, p. 398

- ^ Romero, pp. 257–258

- ^ Romero, pp. 258–259

- ^ McGuire, p. 215

- ^ Romero, pp. 267–268

- ^ Hedges, p. 246

- ^ Romero, p. 276

- ^ Romero, p. 264

- ^ Reato, pp. 58–59

- ^ Romero, pp. 285–286

- ^ Reato, p. 73

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 26–27

- ^ Lagleyze, p. 27

- ^ Reato, p. 59

- ^ Reato, pp. 61–62

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 27–29

- ^ "Cristina Kirchner, presidenta" [Cristina Kirchner, president] (in Spanish). La Nación. 29 October 2007. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ Clifford Kraus (31 March 2009). "Raúl Alfonsín, 82, Former Argentine Leader, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ "Un homenaje multitudinario en la calle" [A populated homage in the streets]. La Nación (in Spanish). 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Murió María Lorenza Barrenechea, la esposa de Raúl Alfonsín". Clarín (Argentine newspaper). 6 January 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ a b Lagleyze, p. 29

- ^ "Líderes mundiales envían sus condolencias" [Global leaders send their condolences]. La Nación (in Spanish). 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b Constanza Longarte (2 April 2009). "Historiadores destacan el papel de Alfonsín como restaurador de la democracia" [Historians praise the role of Alfonsín in the recovery of democracy] (in Spanish). La Nación. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Lagleyze, pp. 47–49

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Libros escritos por Alfonsín" [Books written by Alfonsín] (in Spanish). Alfonsin.org. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burns, Jimmy (1987). The land that lost its heroes: the Falklands, the post-war, and Alfonsín. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7475-0002-9.

- Hedges, Jill (2011). Argentina: A modern history. United States: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-654-7.

- Lagleyze, Julio Luqui (2010). Grandes biografías de los 200 años: Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín. Argentina: Clarín. ISBN 978-987-07-0836-0.

- Lewis, Daniel (2015). The History of Argentina. United States: ABC Clio. ISBN 978-1-61069-860-3.

- McGuire, James (1997). Peronism without Perón. United States: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804736558.

- Méndez, Juan (1987). Truth and Partial Justice in Argentina. United States: Americas Watch Report. ISBN 9780938579342.

- Romero, Luis Alberto (2013) [1994]. A History of Argentina in the Twentieth Century. United States: The Pennsylvania University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-06228-0.

- Rock, David (1987). Argentina, 1516–1987: From Spanish Colonization to Alfonsín. United States: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06178-0. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Tedesco, Laura (1999). Democracy in Argentina: Hope and Disillusion. United States: Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7146-4978-8.

External links

[edit] Media related to Raúl Alfonsín at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Raúl Alfonsín at Wikimedia Commons Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: Raúl Alfonsín

Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: Raúl Alfonsín Spanish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Raúl Alfonsín

Spanish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Raúl Alfonsín- Official site Archived 13 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Biography by CIDOB Foundation (in Spanish)

- Discurso del presidente Raúl Alfonsín (in Spanish)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1927 births

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century Argentine lawyers

- 20th-century Argentine politicians

- 20th-century presidents of Argentina

- Argentine people of Falkland Islands descent

- Argentine people of Galician descent

- Argentine people of German descent

- Argentine people of Spanish descent

- Argentine people of Welsh descent

- Argentine political writers

- Argentine Roman Catholics

- Burials at La Recoleta Cemetery

- Collars of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Deaths from lung cancer in Argentina

- Illustrious Citizens of Buenos Aires

- Members of the Argentine Chamber of Deputies elected in Buenos Aires Province

- Members of the Argentine Senate for Buenos Aires Province

- National University of La Plata alumni

- People from Chascomús

- Presidents of Argentina

- Radical Civic Union politicians

- University of Buenos Aires alumni